In his book Inner Vision: An Exploration of Art and the Brain , neurophysiologist Semir Zeki analyzes recent research into what goes on inside the brain while a person is looking at artwork.

, neurophysiologist Semir Zeki analyzes recent research into what goes on inside the brain while a person is looking at artwork.

One chapter of the book takes up the question of how the brain responds differently to abstract art compared to representational art.

In both kinds of art, the primary areas of the visual cortex become activated as low-level processing begins, as one might expect. But with representational artwork, other parts of the brain come into play as well. (Above: ISM/Science Photo Library. Below: William Merritt Chase, "Still Life with Vegetables")

Zeki states the general rule: “All abstract works activate more restricted parts of the visual brain than narrative and representational art. This probably reflects the general organization of the visual brain, in which each of the parallel processing systems consist of several stages, with each stage constructing the figure at a given level of complexity.”

“The complete figure, as opposed to the ‘building blocks’ constituting the figure, mobilizes higher areas of the visual brain and in particular areas within the inferior temporal cortex. Some of these areas are clearly specialized for object recognition and are activated by views of objects, no matter how these objects are defined visually.”

Other types of art stimulate the brain in distinctly different ways. For example, portrait painting mobilizes a cortical region called the fusiform gyrus that is devoted to facial recognition. Yet another area nearby is devoted to the recognition of expression in faces. (Above: self-portrait by Thomas Couture.)

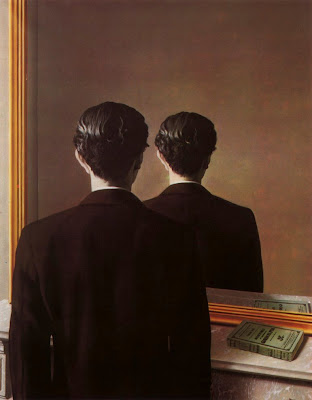

Surrealist paintings activate a part of the frontal lobe that serves to resolve conflicts. Zeki says that this is “an area that monitors the incoming information for any conflict with previous experience.”

A surrealistic image, such as this one by Magritte, presents “a conflict to resolve—the conflict of the immediate view with the record of past experiences, and the frontal lobe seems to be implicated in the resolution of such conflicts.”

In a painting such as this one, showing people in the midst of some meaningful action, many parts of the brain are activated, including not only all the areas mentioned so far, but also the mirror neurons in the prefrontal cortex. This is the "muscle memory" part of the brain that automatically fires when you identify with an action someone else is doing. (Above: Tom Lovell)

It might appear that Zeki’s argument is designed to somehow disparage abstract art as a lesser form than representational art, but that’s definitely not the case. Zeki is evidently fascinated by many different types of art: abstract art, fauvism, cubism, surrealism—and presumably comics and caricature. Each kind of art seems to match up with different aspects or stages of visual processing in the brain.

Whether they work representationally or not, all kinds of artists are natural allies of brain scientists. Most artists are not conscious of the science of neurophysiology. Nevertheless, their pictures give us pleasure because they resonate with different neural phenomena occurring in our brains when we try understand the world with our eyes. Some drawings even seem to reflect how our brains our structured.

For example, the scale distortions of this caricature by Daumier match up pretty well with the uneven distribution of body parts in the classic Penfield cortical homunculus. It's as if Daumier is giving external form to our internal architecture.

Blog reader M. D. Mattin, in a recent comment on this blog, puts Zeki’s argument this way:

Whether they work representationally or not, all kinds of artists are natural allies of brain scientists. Most artists are not conscious of the science of neurophysiology. Nevertheless, their pictures give us pleasure because they resonate with different neural phenomena occurring in our brains when we try understand the world with our eyes. Some drawings even seem to reflect how our brains our structured.

For example, the scale distortions of this caricature by Daumier match up pretty well with the uneven distribution of body parts in the classic Penfield cortical homunculus. It's as if Daumier is giving external form to our internal architecture.

Blog reader M. D. Mattin, in a recent comment on this blog, puts Zeki’s argument this way:

“Our visual experience is the final product of a chain of events beginning at the retina and involving multiple stages of increasing specificity to achieve a mental representation of reality; a work of art can intersect the chain at any point and substitute an external stimulus for the internal model. In order to perceive, say a red truck, the brain passes the stimulus though a series of filters or detectors; one stage might to be the identification the shape as a red rectangle. When we see an abstraction of a simple red rectangle, it stimulates our red rectangle detector directly, which apparently gives us pleasure. I've enjoyed a new found appreciation of abstract art since reading that, as well as a keener enjoyment of simple shapes and colors in the world - every red truck now tickles my red rectangle module."

LINKS

Web summary: "Art and the Brain" by Semir Zeki

Previously on GurneyJourney: Interview with Prof. Zeki on Neuroesthetics

Thanks to OldCarGuy for the Lovell

Previously on GurneyJourney: Interview with Prof. Zeki on Neuroesthetics

Thanks to OldCarGuy for the Lovell

Thanks, MD Mattin

Không có nhận xét nào:

Đăng nhận xét