Thursday's post about the painting machine called

Vangobot brought on a lively discussion about the similarities and differences between human painters and programmed machines.

As many of you observed in the comments, Vangobot executes physical paintings, but the results are only as good as the instructions it receives. As a result, it's easy to dismiss Vangobot as a kind of fancy inkjet printer.

Machines like Vangobot may develop the hand skills to manipulate the brushes and paints, but will they ever have artistic judgment? Is it possible for a computer to be programmed to see and interpret the world in the same way that an experienced painter does?

These are qualities of the "eye" or "mind" or even the "soul" more than the "hand." Blog reader M.P. invoked a quote from nineteenth century drawing instructor James Duffield Harding who characterized the great artist as having an instinct for "selection, arrangement, sentiment, and beauty" rather than just replicating reality.

Let's have a look at a photograph of two people in a parklike setting. How would an experienced painter transform this image?

Note the difference in this master painter's interpretation. The details in the faces are accurately drawn, but rougher brushes are used for the foliage. The drapery is painted efficiently with big slashing strokes. The sky is painted loosely with spots of light. The sidewalk tiles are in perspective, but they're just suggested with thin dashing strokes. The colors are warmed up and intensified.

For a computer to do this, it would have to understand what it was looking at, and have an instinct to do all these subjective interpretations. It would need to be able to handle a lot of brushes in a variety of ways depending on what forms it was painting.

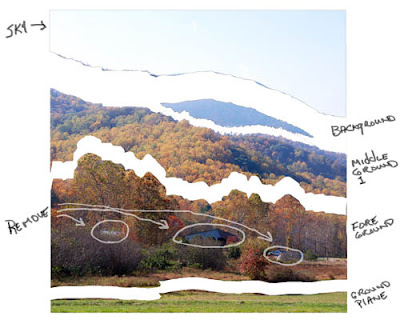

Let's look another example, a photo of a landscape scene composed of sky, trees, water, and rock.

The experienced painter uses a variety of paint handling depending on material. The water uses long horizontal strokes, the rocks are done with flat brushes, and the ducks are painted carefully with small brushes.

Note how different this is than an off-the-shelf "

artistic paint daub filter" from Photoshop, which merely translates everything into blobby strokes indiscriminately across the whole image, without regard to the areas that are psychologically important, such as the faces.

Now what if I told you that the "master painter" of all of the examples is a computer?

The creators of the program are Kun Zeng, Mingtian Zhao, Caiming Xiong, Song-Chun Zhu from Lotus Hill Institute and University of California, Los Angeles. The goal for the software was to interpret photographs in painterly terms.

The process begins with "image parsing," where the scene is divided and grouped into various areas of unequal importance and of unequal character, such as foliage, branches, drapery, and faces. Each region of the painting has different meaning to a viewer and therefore requires a different paint handling. This visual meaning is known in the field of artificial intelligence as "image semantics."

The image parsing software works like the facial recognition system in a modern digital camera, but this system does it at a much more sophisticated level, recognizing and classifying various elements in categories such as:

face/skin, hair, cloth, sky/cloud, water surface, spindrift, mountain, road/building

rock, earth, wood/plastic metal, flower/fruit, grass, leaf, trunk/twig, background, and other.

Image parsing is similar to what a human artist does. Painter Armand Cabrera wrote about this recently in his post "

Learning to See."

The authors of the computer program assigned the computer to use a hierarchy of as many as 700 different brushes for each of these forms, with various settings for opacity (depending on whether it's painting a cloud or a rock), stroke direction, dryness and wetness, and, of course color.

The strokes are applied differently depending on the forms, and they're overlapped spatially, painting from the background to the foreground so that the objects in front "occlude" or paint across the ones behind.

The colors in the painterly images are shifted according to a statistical observation that the typical hue and chroma distribution of colors in photos (left) differ from those of paintings (right). Paintings have less blue and green, and more yellow and red.

What does this mean for traditional painters? Should we welcome it or be worried? If this software is hooked up to a Vangobot, anyone could buy a really nice wedding portrait painted in oil from a decent wedding photo. A portable Vangobot with this software could start winning plein air competitions, just as computers have won chess matches.

Is there some skill set that is out of reach of programmed machines? As Anonymous mused in the comments of the last post, "maybe it's along the lines of caricature, and the intensification of forms and space and color and emotions and beauty and mystery?" Will computers ever achieve the higher level judgments, what Harding referred to as "selection, arrangement, sentiment, and beauty?"

I would be inclined to say yes, yes, yes, and yes. Computers will learn to caricature and they'll do a good job at it. They will learn to paint science fiction and fantasy, and to do Van Gogh or Picasso transformations. Anything that can be deconstructed can be programmed. The more these computers advance, the better we understand what we do as painters. As blog reader Todd said so well: "Robots will only be able to represent as much of humanity as we understand about ourselves."

Despite it all, I do believe that there is something elusive, some element of real genius in great artists that will always stay beyond the reach of materialistic or deconstructive analysis. The greatness of Mozart and Rembrandt and Shakespeare can never be matched by a computer. And for more earthbound practitioners like me, I can take comfort in the faith that other humans will always enjoy works that are filtered through the human consciousness and the human hand, just as we prize home cooking, hand knitting, wooden boats, and folk music.

I believe we should congratulate Kun Zeng, Mingtian Zhao, Caiming Xiong, and Song-Chun Zhu and applaud their accomplishment. These painting systems are not faceless robots, but the creations of amazingly bright people. The one thing that is certain is that these new systems will put certain kinds of artists out of business, they will redefine what we hand-skilled artists do, and the tools will bring to the table new creative opportunities that we can't even imagine yet.

-------

Thanks,

Jan Pospíšil for linking me to this paper.

Video showing Photoshops "

artistic filters,"

Previously:

Vangobot